RODELINDA, REGINA DE' LONGOBARDI (HWV 19)

Libretto: Nicola Haym, after Antonio Salvi

First performance: 13th February 1725, King's Theatre, London

Cast

- Francesca Cuzzoni (Soprano)

- Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" (Alto castrato)

- Francesco Borosini (Tenor)

- Anna Vicenza Dotti (Contralto)

- Andrea Pacini (Alto castrato)

- Giuseppe Maria Boschi (Bass)

Synopsis

Act I

The opera opens with Rodelinda’s lament for Bertarido, the husband she believes to be dead. “Ho perduto il caro sposo”, she sings, voicing the tragedy that is the central fact of her life as she sits alone and weeping in the palace. Though Rodelinda will pass through grief, misery and fury, her fidelity to Bertarido’s memory is inflexible and defines her every action until their joyous reunion.

She is disturbed by the arrival of Grimoaldo, the usurper of her husband’s throne, who declares both his love and his desire to marry her. Garibaldo, his henchman, arrives, and suggests that his patron free himself of the woman he once promised to marry, Eduige, who complicates the plot by also being Bertarido’s sister. But Garibaldo – falsely, since he is a villain – protests his love to Eduige, believing she will help him attain the throne, to which she has a claim so long as Rodelinda’s son, Flavio, is still a minor.

A disguised Bertarido appears at his own tomb and reads the inscription. He reflects upon the hollow splendour of man’s ambitions in a long accompanied recitative, “Pompe vane”. Longing for Rodelinda, he sings the meltingly beautiful aria “Dove sei”, declaring that only in her presence can he find consolation for his sorrow.

Unulfo appears but is unable to comfort his friend, the devastated Bertarido. They hide when they hear Rodelinda approach the tomb and give voice to her misery in the aria “Ombre, piante”, then are forced to listen to Garibaldo threaten her: either she marries Grimoaldo or Flavio will die. She agrees to the union but vows that her first request as queen will be the head of Garibaldo, the Iago-like counsellor of Grimoaldo. Her sober mournfulness now turns to something more passionate: “Morrai, sì” is a surprisingly sprightly hymn to future vengeance.

But it is not enough to persuade Bertarido of her fidelity when, from a hidden place, he hears her agree to marry his enemy Grimoaldo. Immediately certain of her infidelity, he launches into the bitter “Confusa si miri”. He vows to appear to her when she is married.

Act II

The importunate Garibaldo is surprised at Eduige’s consent to marry him since she has lost Grimoaldo. Meanwhile Rodelinda, tormented past bearing by his overtures, turns on Grimoaldo with a test of his own monstrosity and declares that she will marry him only if he will murder her son in front of her eyes (thus proving his absolute villainy). Unulfo urges him to refuse; Garibaldo urges him to accept. The distressed Grimoaldo hastens from the scene, leaving Garibaldo to plot his master’s downfall.

Bertarido stands in “a pleasant landscape” and gives himself over to the pathetic fallacy: nature’s sounds and sights mirror his own anguish. Eduige is reunited with her brother, astonished to find Bertarido alive and elated to hear that his sole aim is to save his wife and son (and not to reclaim the kingdom). Unulfo appears and assures Bertarido that his wife is in fact faithful to him, and both his heart and his aria turn joyful in “Scacciata dal suo nido”.

Unulfo then goes to Rodelinda and assures her that her husband still lives and soon will return to her: “Ritorna, o caro” gives voice to her rhapsodic joy and longing. Bertarido seeks her out in the palace and kneels to beg her forgiveness for having doubted her constancy. They are no sooner united than discovered, as Grimoaldo arrives.

To save Rodelinda’s reputation, Bertarido reveals that he is her husband, but, in order to protect him, she denies this. Grimoaldo, uninterested in the man’s identity, condemns him to prison and certain death. The last the loving couple believe they will know of one another are the final moments of “Io t’abbraccio”.

Act III

Eduige gives Unulfo a key to rescue the imprisoned Bertarido while Garibaldo, bad to the very end, urges Grimoaldo to kill him. In a dungeon, Bertarido reflects upon his fate in “Chi di voi”, the music as restless as his spirit. His lament is interrupted by both a sword dropped down to him by Eduige and the arrival of Unulfo with the key: mistaking his friend for the executioner, Bertarido stabs and wounds him. No sooner has he realized his mistake than distant voices force them to flee. They leave behind a bloody cloak, which the arriving Rodelinda takes to be that of her husband. Certain that he is dead, she lapses into re-doubled grief in “Se ’l mio duol”, begging God to strike a dagger through her heart.

Grimoaldo takes an honest look at the beast he has become, longs for a shepherd’s simple life and seeks escape in sleep. Garibaldo, discovering him, tries to kill him but is prevented by Bertarido: too noble to allow his enemy Grimoaldo to fall victim to treachery, Bertarido drives Garibaldo off and kills him.

The waking Grimoaldo is confronted by his enemy’s declaration (in one of Handel’s greatest stand-and-deliver arias, “Vivi, tiranno”), witnessed by the entering Rodelinda, that Bertarido has spared him and saved his life. Proof of such clemency moves Grimoaldo to repentance: he gives Bertarido his wife, his son and his throne, and the royal lovers are reunited to general rejoicing.

Donna Leon

rev. © 2005 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

Context

An immediate success when first performed, Rodelinda was the third great opera Handel had written in twelve months – an astonishing achievement. It followed on the success of Giulio Cesare and Tamerlano, and once again starred the ideal pairing of the castrato Senesino and soprano Francesca Cuzzoni. Of Cuzzoni’s appearance in Rodelinda Horace Walpole said: ‘She was short and squat, with a doughy cross face, but fine complexion; was not a good actress; dressed ill; and was silly and fantastical. And yet on her appearing in this opera, in a brown silk gown trimmed with silver, with the vulgarity and indecorum of which all the old ladies were much scandalised, the young adopted it as a fashion, so universally, that it seemed a national uniform for youth and beauty’.

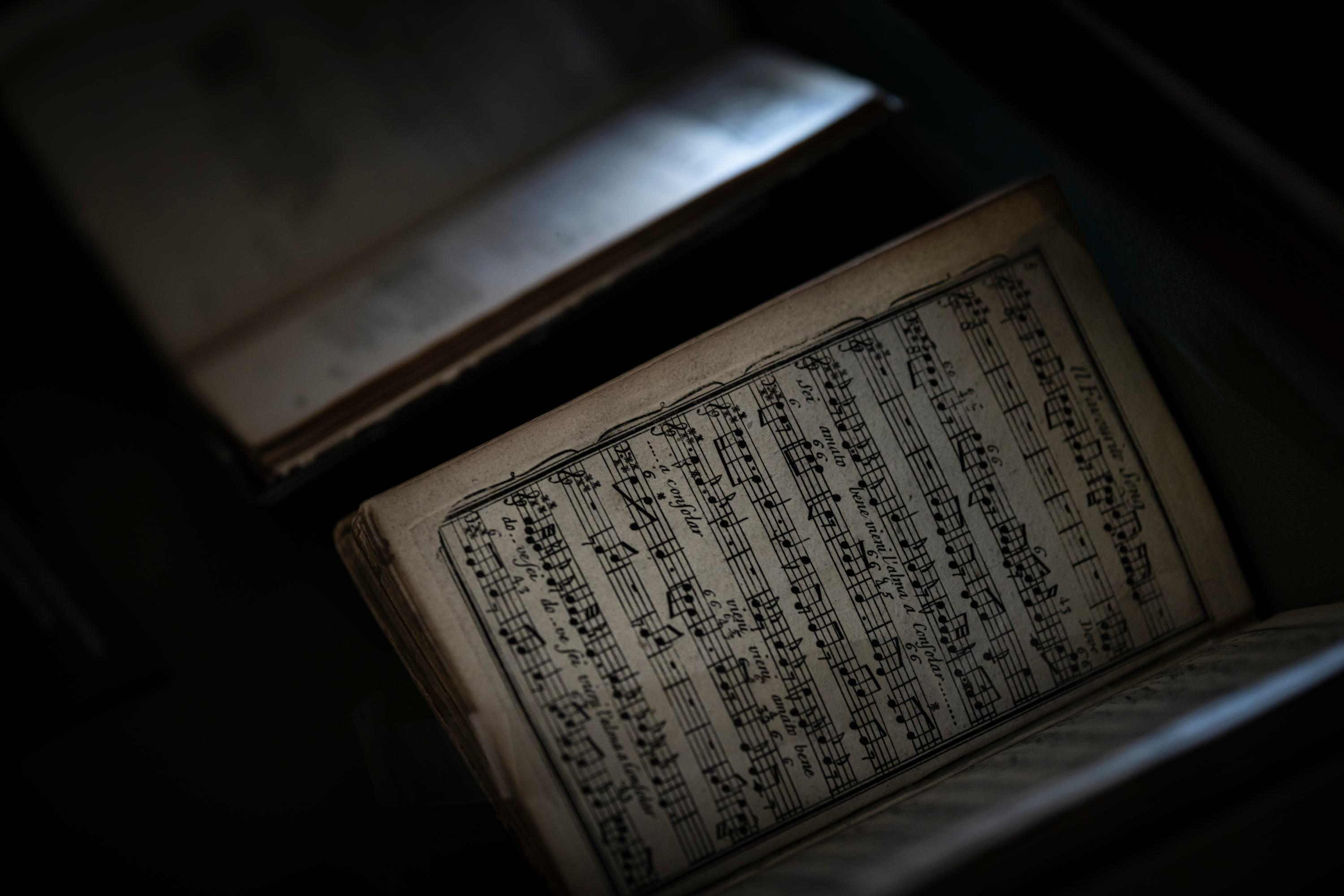

In May 1725 Handel published the full score of Rodelinda, relying for the first time on a group of subscribers to cover the costs of setting and publication. Over the following years eight operas, one choral ode (Alexander’s Feast) and the Concerti Grossi Op. 6 would be published in the same way. Among the first subscribers were Charles Jennens, who in 1741 provided Handel with the libretto for Messiah, and John Rich who at the time was manager of the Theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. In 1728 Rich was the producer of John Gay’s enormously popular The Beggar’s Opera, and built the first opera house in Covent Garden on the proceeds.

In April 1725 Handel’s name appeared for the first time in the Rate-Books of the Parish of St. George Hanover Square: ‘George Frederick Handell, Rent £35. First Rate 17s. 6d’.